I've touched quite a few times on my thoughts when it comes to the morality of human beings who commit horrendous acts. I don't believe in words like "evil" and "inhuman" simply because they imply that the action is beyond human capabilities and comprehension. I believe that for as long as we fail to recognise certain behaviours as inherently human, we fail to understand the causes and therefore we let down ourselves and those that we condemn.

I said in my first post that I wanted to develop my opinions on the death penalty through open discussion. After I wrote my blog entry on Josef Fritzl and the international hatred that was aimed at him, a few people (who I won't name) broached the subject with me in person. They disagreed, feeling that I was being insensitive to the feelings of those people who were truly affected by what happened. I think my initial response was that I have little sympathy for people who have only had their sensibilities affronted, and that people so willing to judge when their connection to the case is as fleeting as a few articles in the newspaper don't concern me at all. When it comes to the victims and their families, it is a different story all together. I can't possibly imagine the suffering that they are going through, and wouldn't suggest that I could quantify or rationalise that suffering.

When I was interviewed for my internship in the U.S. I was asked a question that took me a few days to realise the answer to:

There is a man who has been arrested for murder in the second degree and sentenced to life in prison. While incarcerated, he smuggles a gun into the prison and shoots a prison warden to death. He is sentenced to death for the crime and while on death row he fashions a knife and stabs another warden to death. How would you justify to the families of these 3 victims that this man doesn't deserve to die? Every day this man is a risk to the lives of people who are just getting up and going to work and trying to live their life.

The answer, I realised is that there is no answer. One of our most defining qualities as human beings are the values we have been brought up with. In a situation such as this, you do not justify your values to the families of those 3 victims. You show humility in the face of their suffering and you swallow your pride. You can't reason with that sort of anguish and nor should you try.

In that case, is it ever justifiable to engage in discussion about the morality of murderers and rapists?

I read an article in the A2 (The Age) on Saturday entited

"Monster Like Us: Is evil knowable, or does morality demand that we deny its humanity?" by Maria Tumarkin, that examined this very question in the context of the Holocaust. The Holocaust was a crime that claimed up to 6 million souls, and has had such a wide impact, has touched so many lives directly, that perhaps it is wrong to examine it objectively and dispassionately. This post draws heavily from the article that appeared in The Age.

This article was of great interest to me, especially since I had studied the Holocaust in university and had written a few papers on whether or not "ordinary" Germans were capable of committing the atrocities or if they were inherently "evil" people.

I realised that this is an issue that has divided human thought and feeling for centuries. From Rousseau who believed that we must make "evil" intelligible, to Voltaire who stated that our morality demands that we don't.

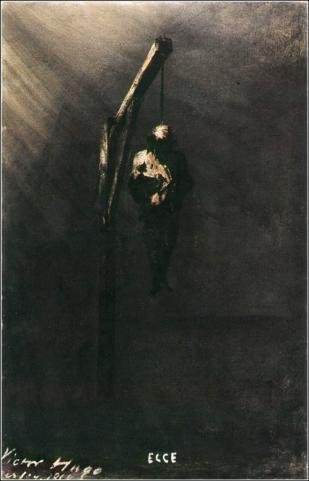

Hannah Arendt is no doubt one of the most controversial figures on the subject of "moral relativism". She observed the trial of Eichmann, who was eventually hung by the state of Israel. She wrote on the "banality of evil":

"It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never radical, that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface... That is its banality. Only the Good has depth and can be radical."

Opinions like this always spark angry reactions, labeling them as apologist, revisionist or trivialist. More so, how can someone who has never been even remotely close to such a tragedy comment on the nature of evil. The article quoted a poem written by Aushwitz survivor Charlotte Delbo that really struck me:

"O you who know / did you know that you can see your mother dead / and not shed a tear... / Did you know that suffering is limitless / that horror cannot be circumscribed / Did you know this / You who know."

It appears there are two reasons that challenge those who seek a human element to seemingly inhuman acts. There are those who would tell you that until you have experienced such suffering yourself you are not capable to speak of it. And others who threaten that to stare evil in the eye, shake its hand and treat it with equal consideration is not far from courting the devil itself.

Before reading this article my opinions were too absolute. I believed that nobody had a monopoly on suffering, that nobody had the right to consider another human being as inhuman or evil. The author, Maria Tumarkin made it quite clear that a battle rages inside of her head:

"And so the two voices in my head grow louder. There is no peace. Not even a prospect of ceasefire. Such blind foolishness fuelled by the self-congratulatory missionary zeal to insist that the darkness is knowable, always ready to yield meaning and to be illuminated. Such pig-headed denial of what makes us human to insist that the darkness is impenetrable, off-limits."

The possibility that arrogance is the driving factor behind delving into the unknown is an interesting point of view. Perhaps it is a denial of a natural human reaction to rationalise "evil" acts, and to do so is nothing but a "pig-headed" attempt to distance ourselves from our natural emotions. Much like Marlow, who "delved deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness" and experienced first hand "the horror" of the human condition, we are delving into elements of the human psyche which are impossible to rationalise or humanise.

What is the correct answer, the right approach? What I've realised is that there isn't one. But what is necessary is that the nature of humanity is always open for discussion and that absolutism only stifles the discourse. It is inherently human to consider the incomprehensibly cruel acts of others as inhuman, while at the same time it is inherently human to search for humanity when faced with seemingly limitless evil.

Quote of the day:"I think the only answer is to look inside ourselves, not others. The Nazi, the Khmer Rouge, the Rwandan killer is a man who looks like us. That's my only conclusion."

-Francois Bizot